[T]he invisible world remained invisible, insensible except by metaphor. . . .Yet the invisible and the visible are both there, and the opposite of real is not unreal

-Melissa Scott, Night Sky Mine, 8.

I was born in 1955, in a small college town in Idaho, an intensely conservative state in the western U.S. As a queer autistic woman, I failed being “normal.” I began reading at age three. Even worse, while I read everything I could find in the school and public libraries, science fiction and fantasy became my favorite genre from age five on. There was no organized fandom in Idaho then, but I could escape into worlds of possibility that were invisible to everyone but me. Two writers became important to me not only in terms of escaping from the world around me but also in shaping my future career: Joanna Russ and Melissa Scott.

I was born in 1955, in a small college town in Idaho, an intensely conservative state in the western U.S. As a queer autistic woman, I failed being “normal.” I began reading at age three. Even worse, while I read everything I could find in the school and public libraries, science fiction and fantasy became my favorite genre from age five on. There was no organized fandom in Idaho then, but I could escape into worlds of possibility that were invisible to everyone but me. Two writers became important to me not only in terms of escaping from the world around me but also in shaping my future career: Joanna Russ and Melissa Scott.

Today, I want to talk about Melissa Scott. She began publishing in 1984 and has, at the time of this writing, published nearly fifty books in multiple sub-genres of the fantastic: cyberpunk, fantasy, fantasy-mystery, feminist science fiction, and space opera. Her most recent novel, Waterhorse, was released June 1, 2021. She has won ten awards, having been nominated twenty-nine times, starting with the John W. Campbell (now “Astounding”) Award for Best New Writer. Her awards include: the James Tiptree Jr. (now Otherwise) Award, the Gaylactic Spectrum Award, and the Lambda Award for Trouble and Her Friends (1994), Shadow Man (1995), Point of Dreams (2001), and Death by Silver (2013).

Today, I want to talk about Melissa Scott. She began publishing in 1984 and has, at the time of this writing, published nearly fifty books in multiple sub-genres of the fantastic: cyberpunk, fantasy, fantasy-mystery, feminist science fiction, and space opera. Her most recent novel, Waterhorse, was released June 1, 2021. She has won ten awards, having been nominated twenty-nine times, starting with the John W. Campbell (now “Astounding”) Award for Best New Writer. Her awards include: the James Tiptree Jr. (now Otherwise) Award, the Gaylactic Spectrum Award, and the Lambda Award for Trouble and Her Friends (1994), Shadow Man (1995), Point of Dreams (2001), and Death by Silver (2013).

And yet a number of her novels have gone out of print, and academic scholarship on feminst sf and cyberpunk/cyberfiction (the genres of her best-known works) has paid relatively little attention to her fiction. My favorite are her seven cyberpunk/cyberfiction novels published between 1992 and 2000.[1] These novels center characters in oppressed and marginalized groups, primarily focusing on queer communities and families of choice, while incorporating elements historically and currently associated with straight masculinist science fiction, especially the 1980s cyberpunk. Scott was creating a queer tradition in the last decade of of the 20th century as the backlash against civil rights, women’s rights, and gay rights began to build.

The worlds of science fiction have become more visible in the 21st century, a change that I celebrate regularly. Two award-winning sf series in recent years have explored themes of AI, cyborgs, gender, corporate capitalism, and imperialism to great acclaim. First was Ann Leckie’s award-winning Imperial Raadch trilogy: Ancillary Justice (2013), Ancillary Sword (2014) and Ancillary Mercy (2015).

A few years later, Martha Wells began publishing her award-winning Murderbot series: All Systems Red (2017), Artificial Condition (2018), Rogue Protocol(2018), Exit Strategy (2018), Network Effect (2020), “Home: Habitat, Range, Niche, Territory” (2021), and Fugitive Telemetry (2021).

I love both series for many reasons including the extent to which they resonate with Scott’s queer cyberfiction. I do not know if Leckie or Wells ever read Scott’s sff: if I write a longer essay, I will probably muster enough courage to ask them if they did.

Scott’s work was ahead of her time in how she showed not only a wide range of queer characters, gender identities, and orientations, characters who come together to live and love in future corporate and technological dystopias. Re-reading them now, as I have been doing since the pandemic started, I am struck by how relevant they are. Scott’s worldbuilding was unusual in her attention to complexities of intersectional structures, exploring multiple ways in which characters are marginalized and/or privileged due to class, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation.

My current favorite among the group is Night Sky Mine which is currently out of print and seems to have few reviews of any length or complexity online. There will be some spoilers.

My current favorite among the group is Night Sky Mine which is currently out of print and seems to have few reviews of any length or complexity online. There will be some spoilers.

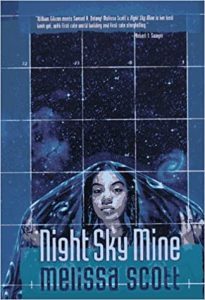

The novel’s title refers to the name of a mining company. The original cover illustration features one of the protagonists, Ista Kelly. A dark-skinned young woman is shown against a starry sky overlaid with a grid; the image creates a metaphorical interpretation of the title as focusing on her claiming the “night sky,” her identities and heritage.

From the opening pages, the visible (material) world of the novel reflects conventions of space opera (humans spread over space, alien species, living on planets and in space stations, mining asteroids for resources, etc.). Scott’s worldbuilding not only includes the apparently familiar universe of the genre, seen through the perspectives of marginalized peoples, but also the invisible world, the virtual world.

The novel is set in a future which has already experienced one Crash when the inhabitants of an earlier virtual world took over the networks and had to be controlled through the creation of a new language, VALMUL. The current world is one in which significant resources, economic and human, corporate and political, are spent policing and controlling the virtual world as well as economically precarious groups.

Some believe that the human world is reality, and the invisible world with all its programs is a metaphor, a byproduct of the technology; others understand the invisible world as more than a metaphor, as a place in which the programs are evolving and becoming more complex, working toward the potential AI which could bring about a second Crash and possibly the destruction of the material world.

Within this world, Scott sets four point of view characters, two adolescent girls and two adult men, all of whom are queer, all of whom are from different classes and ethnic groups. The girls are in the early stages of thinking their friendship might become a partnership while the men are contracted partners struggling with the pressures on their relationship due to their different backgrounds. All four come together to deal with a feral program that threatens to take over the invisible world, an event that changes their lives and circumstances.

I almost hope I am wrong, that Scott’s work is not as invisible as have come to believe during the years when I could not order her books for my classes. But if I am right, I hope that others will join me in her various worlds.

Works Cited:

“Ann Leckie.” Science Fiction Awards Database

“Leckie, Ann.” Ann Leckie

Martha Wells.” Science Fiction Awards Database.

“Melissa Scott.” Fantastic Fiction.

“Melissa Scott.” Science Fiction Awards Database

Prell, Lettie. “Women Writers Winning Hugo Awards: A History.” Lettie Press. Apr. 16, 2017.

Scott, Melissa. Burning Bright, Tor, 1993

—. Dreamships, Tor, 1992.

—. Dreaming Metal, Tor, 1997.

—. The Jazz, Tor, 2000.

—. Night Sky Mine, Tor, 1996.

—. The Shapes of Their Hearts, Tor, 1998.

—. Trouble and Her Friends, Tor, 1994.

“Summary Bibliography: Joanna Russ.” Internet Science Fiction Database.

“Summary Bibliography: Melissa Scott.” Internet Science Fiction Database.

Wells, Martha. “Home: Habitat, Range, Niche, Territory.” Tor.com. Apr. 19, 2021.

—. Worlds of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

[1] Trouble and Her Friends, Dreamships, Dreaming Metal, The Shapes of their Hearts, Burning Bright, Night Sky Mine, and The Jazz

*************************************************************************************

This article was brought to you by Robin Reid in association with Promotions.

Robin Reid is living the dream of being retired with lots of time to write about fantasy and science fiction and no more grading or writing academic reports. She is happy with either she/her or they/their pronouns (just not he/him because too many people assume “Robin” = a man!).

We are the Bid Team for Glasgow in 2024 – A Worldcon for Our Futures. We are part of the vibrant Worldcon community. We would love to welcome you to Glasgow and the Armadillo Auditorium for the 2024 Hugo Awards. Please consider supporting us.