A couple of months ago I came to the sudden realisation that, for this gay lad, fantasy and religion are one and the same thing. Not in the sense, of course, that both refer to things that don’t exist, but rather in that both have always filled me with the same feeling – a strange mix of awe and cosiness.

A couple of months ago I came to the sudden realisation that, for this gay lad, fantasy and religion are one and the same thing. Not in the sense, of course, that both refer to things that don’t exist, but rather in that both have always filled me with the same feeling – a strange mix of awe and cosiness.

Both fantasy and religion are awakened by the realisation that something in this world is just not enough, that we don’t quite fit in with things as they are. Somewhere deep inside, we are huge, even infinite beings that yearn for infinity. Expansive, eager things we are. We dream, we hope, and therefore we imagine, precisely because the sharp edges of this cubicle-like life of ours are far, far too narrow.

Of course, this is especially true for queer people: we don’t even fit in the boxes within the box, in the categories that organise people and map out biographies. Conformity is the hallmark of mainstream decency: you stay in your lane, you don’t overstep your marks, you push forward, you do your duty and die modestly. For us queers, this depressing programme is not just depressing: it’s impossible. So, we feel at home with the dreamers and the wanderers, the mystics and the craziest of revolutionaries. That’s why, perhaps, we gravitate so easily towards fantasy and, surprisingly, towards spirituality or religion. In fantasy, we learn that there is a space of inner freedom and yearning where we can exist and thrive.

In religion, we turn our imagination and hopes into prayer, crying into the night that our dreams may come true. Both are realms in which language pushes us forward to the very limit of its own capabilities, leaving us at the point in which it’s exhausted. And there’s where we find ourselves truly joyful: standing together in the twilight, at the brink of the starry Unknown. Both fantasy and religion (good religion, true religion) demand that thing we have in hoards: expansivity, eagerness… ‘Go on,’ they whisper in unison, ‘dream on your wildest dreams: we can take it, and we’ll still surprise you.’ Because wonder is the stuff of fantasy, as it is the stuff of religion. That which is not in the programme, which is profoundly ‘indecent’ precisely because it goes beyond what we are allowed to expect from this world.

In religion, we turn our imagination and hopes into prayer, crying into the night that our dreams may come true. Both are realms in which language pushes us forward to the very limit of its own capabilities, leaving us at the point in which it’s exhausted. And there’s where we find ourselves truly joyful: standing together in the twilight, at the brink of the starry Unknown. Both fantasy and religion (good religion, true religion) demand that thing we have in hoards: expansivity, eagerness… ‘Go on,’ they whisper in unison, ‘dream on your wildest dreams: we can take it, and we’ll still surprise you.’ Because wonder is the stuff of fantasy, as it is the stuff of religion. That which is not in the programme, which is profoundly ‘indecent’ precisely because it goes beyond what we are allowed to expect from this world.

Fantasy is not about magic (if by magic we mean a sort of alternative science, bound to its own rules and limits), but about miracles. It might be surprising that I say religion is a good place for queer people: so many of us have been hurt horribly by religious institutions, authorities and communities. But that’s not religion in its truest sense, that wild thing that breaths meaning into the apparently meaningless, that makes nameless things into things and then into sacred things; that makes a house into a home, and a man into one’s beloved. That thing that hurt us is the petrified carcass of a noble and beautiful being, hard and sharp as dry coral. That awful thing is what’s left when religion starves to death, what ‘decent’ people build in the desiccated innards of dead religion in order to galvanise their poor, boring, mind-numbing worldviews. It doesn’t matter that most religion in our days is dead religion. The fact that’s widespread does not make it true.

Queer people will tell you: there’s divinity when your friend transitions and you see their first true smile and you finally learn their true name; there’s divinity when you fall madly in love with your best friend and you kiss for the first time; there’s divinity in the fleshy, most human wisdom that our queer elders passed down from the times of Stonewall and the AIDS pandemic. There’s miracle, we know it, when the strangeness and ‘indecency’ of life hits you in the face, wakes you up to your truest self, and it’s like you are breathing clean air for the first time, and you know it: you have entered a realm of fantasy – of hope and yearning – that is your true motherland. I know it.

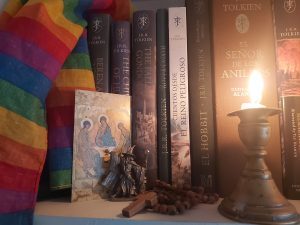

When I was still in the closet, there was a backdoor that opened into Narnia and Middle Earth and that galaxy far far away, and my own worlds of hope and unhinged yearning. I think everybody knew it, that I was drinking from some hidden well – the decent people tried to shut the door close, and when they couldn’t, they tried to colonise my imagination with their dull allegorism. But they could not, thanks be to God. And when I was finally ready to come out, all of it come out with me, like the armies of the Valar: I am a queer Christian fantasist, and I honestly feel invincible.

*************************************************************************************

This article was brought to you by Joseph Michael Brennan in association with Promotions.

Joseph Michael Brennan (AKA Exequiel Monge Allen) [he/him] is a Chilean author. Between 2016 and 2018, he published the fantasy trilogy Las Memorias del Juramento (“Memoirs of the Oath”) with Penguin Random House Chile. The first volume was awarded the national Marta Brunet Prize to the best young-adult piece of 2016. He is also a Celtic Studies’ scholar.

We are the Bid Team for Glasgow in 2024 – A Worldcon for Our Futures. We are part of the vibrant Worldcon community. We would love to welcome you to Glasgow and the Armadillo Auditorium for the 2024 Hugo Awards. Please consider supporting us.